Three Rivers Stadium

The Blast Furnace The House that Clemente Built | |

| |

View from south in 1999 | |

| |

Location in the United States Location in Pennsylvania | |

| Address | 792 W General Robinson St |

|---|---|

| Location | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°26′48″N 80°0′46″W / 40.44667°N 80.01278°W |

| Owner | Pittsburgh |

| Operator | Pittsburgh Stadium Authority |

| Capacity | Football: 59,000 Baseball: 47,971 |

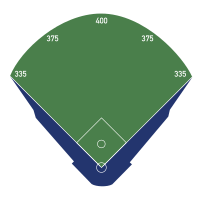

| Field size | Left Field — 335 ft / 102 m Left-Center — 375 ft / 114 m Center Field — 400 ft / 122 m Right-Center — 375 ft / 114 m Right Field — 335 ft / 102 m Wall height — 10 ft / 3 m  |

| Surface | Tartan Turf (1970–1982) AstroTurf (1983–2000) |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | April 25, 1968 |

| Opened | July 16, 1970 |

| Closed | December 16, 2000 |

| Demolished | February 11, 2001 |

| Construction cost | US$55 million ($457 million in 2023 dollars[1]) |

| Architect | Deeter Ritchy Sipple Michael Baker Jr. |

| Structural engineer | Osborn Engineering |

| Services engineer | Elwood S. Tower Consulting Engineers[2] |

| General contractor | Huber, Hunt & Nichols/Mascaro[3] |

| Tenants | |

| Pittsburgh Pirates (MLB) (1970–2000) Pittsburgh Steelers (NFL) (1970–2000) Duquesne Dukes (1971)[4] Pittsburgh Maulers (USFL) (1984) Pittsburgh Panthers (NCAA) (2000) | |

| Designated | November 26, 2007[5] |

Three Rivers Stadium was a multi-purpose stadium in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, from 1970 to 2000. It was home to the Pittsburgh Pirates of Major League Baseball (MLB) and the Pittsburgh Steelers of the National Football League (NFL).

Built to replace Forbes Field, which opened in 1909, the US$55 million ($457 million in 2024) multi-purpose facility was designed to maximize efficiency. Ground was broken in April 1968 and construction, often behind schedule, took 29 months.[6] The stadium opened on July 16, 1970, with a Pirates game. In the 1971 World Series, it hosted the first World Series game played at night. The following year, the stadium was the site of the Immaculate Reception. The final game in the stadium was won by the Steelers on December 16, 2000. Three Rivers also hosted the Pittsburgh Maulers of the United States Football League and the University of Pittsburgh Panthers football team for a single season each.[7][8]

After its closing, Three Rivers was imploded in 2001, and the Pirates and Steelers moved into new dedicated stadiums: PNC Park and Heinz Field (now Acrisure Stadium), respectively.

History

[edit]Planning and construction

[edit]A proposal for a new sports stadium in Pittsburgh was first made in 1948; however, plans did not attract much attention until the late 1950s.[9] The Pittsburgh Pirates played their home games at Forbes Field, which opened in 1909,[10] and was the second oldest venue in the National League (Philadelphia's Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium was oldest, having opened only two months prior to Forbes). The Pittsburgh Steelers, who had moved from Forbes Field to Pitt Stadium in 1964, were large supporters of the project.[9] For their part, according to longtime Pirates announcer Bob Prince, the Pirates wanted a bigger place to play in order to draw more revenue.[11]

In 1958, the Pirates sold Forbes to the University of Pittsburgh for $2 million ($21.1 million today); it wanted the land for expanded graduate facilities.[11] As part of the deal, the university leased Forbes back to the Pirates until a replacement could be built.[12] An early design of the stadium included plans to situate the stadium atop a bridge across the Monongahela River. It was to call for a 70,000-seat stadium with hotels, marina, and a 100-lane bowling alley.[13] Plans of the "Stadium over the Monongahela" were eventually not pursued.[14] A design was presented in 1958 which featured an open center field design—through which fans could view Pittsburgh's "Golden Triangle".[15] A site on the city's Northside was approved on August 10, 1958, due to land availability and parking space,[15][16][17] the latter of which had been a problem at Forbes Field.[9] The same site had hosted Exposition Park, which the Pirates had left in 1909.[18] The stadium was located in a portion of downtown difficult to access;[11] political debate continued over the North Side Sports Stadium and the project was often behind schedule and over-budget.[15][19] Arguments were made by commissioner (and former Allegheny County Medical Examiner) William McCelland that the Pirates and Steelers should fund a higher percentage of the $33 million project ($309.9 million today). Due to lack of support, however, the arguments faded.[15][20]

Ground was broken in 1968 on April 25,[15][21][22] and due to the Steelers' suggestions, the design was changed to enclose center field.[15] Construction continued, though it became plagued with problems such as thieves stealing materials from the building site.[15] In April 1969, construction was behind schedule and the target opening date of April 1970 was deemed unlikely to be met.[23] That November, Arthur Gratz asked the city for an additional $3 million ($24.9 million today), which was granted.[24] In January 1970, the new target date was set for May 29; however, because of a failure to install the lights on schedule, opening day was delayed once more to July 16.[24] The stadium was named in February 1969 for its location at the confluence of the Allegheny River and Monongahela River, which forms the Ohio River.[25][26] It would sometimes be called The House That Clemente Built after Pirates' right-fielder Roberto Clemente.[27]

Opening Day

[edit]In their first game after the All-Star Break in 1970, the Pirates opened the stadium against the Cincinnati Reds on Thursday, July 16; who won, 3–2.[28][29] The team donned new uniform designs for the first time that day, a similar plan was for new "mini-skirts" for female ushers. However, the ushers' union declined the uniform change for female workers.[30] A parade was held before opening ceremonies. The expansive parking lot, both Pirates and Steelers team offices, the Allegheny Club (VIP Club) and the press boxes and facilities were not opened until weeks later due to extended labor union work stoppages. Instead of allowing cars to park, the team instructed fans to park downtown and walk to the stadium over bridges or take shuttle buses. The opening of Three Rivers marked the first time the Pirates allowed beer to be sold in the stands during a game since the early 1960s.[30]

During batting practice on that day, a stray foul ball hit a woman named Evelyn Jones in the eye while she was walking the stadium's concourse. She sued the Pirates and their subsidiary that managed the stadium, arguing that the Baseball Rule, which usually prevents spectators at baseball games from holding teams liable for foul ball injuries, did not apply because she was away from the seating areas and not watching what was going on on the field. A jury awarded Jones $125,000, but it was reversed on appeal. That decision was in turn reversed by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, which agreed with her argument about the Baseball Rule and also noted that the opening to the concourse through which the foul had passed was a purely architectural choice that was not necessary to the game of baseball.[31]

Design and alterations

[edit]

Three Rivers Stadium was similar in design to other stadiums built in the 1960s and 1970s, such as RFK Stadium in Washington, Shea Stadium in New York, Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, the Houston Astrodome, Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, and Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, which were designed as multi-purpose facilities to maximize efficiency.[32][33] Due to their similar design these stadiums were nicknamed "cookie-cutter" or "concrete doughnut" ballparks.[11] The sight lines were more favorable to football; almost 70% of the seats in the baseball configuration were in fair territory.[11] It originally seated 50,611 for baseball,[11] but several expansions over the years brought it to 58,729.[34] In 1993, the Pirates placed tarps on most of the upper deck to create a better baseball atmosphere, reducing capacity to 47,687.[11][35][36]

Three Rivers was the first multi-purpose stadium and the first in either the NFL or MLB to feature 3M's Tartan Turf (then a competitor to the dominant AstroTurf), which was installed for opening day.[37][38] It had a dirt skin infield on the basepaths for baseball through 1972,[28] until converted to "sliding pits" at the bases for 1973.[39] Renovations for the start of the 1983 baseball season included replacing the Tartan Turf with AstroTurf, the center field Stewart-Warner scoreboard being removed and replaced with new seating—while a new Diamond Vision scoreboard with a White Way messageboard was installed at the top of the center field upper deck—and the outfield fence being painted blue from the previous aqua.[40][41] The field originally used "Gamesaver vacuum vehicles" to dry the surface, though they were later replaced by an underground drainage system.[38]

In 1975, the baseball field's outfield fences were moved 10 feet (3 m) closer to home plate, in an attempt to boost home run numbers.[38] The bullpens were moved to multiple locations throughout the stadium's history; however, their first position was also their final one—beyond the right-field fence.[38] A Pittsburgh Post-Gazette story in 1970 stated that the new stadium boasted 1,632 floodlight bulbs.[42]

at Three Rivers

Due to Three Rivers Stadium's multi-purpose design, bands including Alice Cooper, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones, and The Who hosted concerts at the venue.[43][44] On August 11, 1985,[45] Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band hosted the largest concert in Pittsburgh history, when they performed for 65,935 on-lookers.[46] And in 1992, the Pittsburgh Penguins celebrated their second Stanley Cup victory at the Stadium.[44] The stadium hosted various Jehovah's Witnesses conventions, including international conventions in 1973 and 1978, and a centennial conference in 1984. A Billy Graham Crusade took place at Three Rivers in June 1993.[47] The venue also served as the premiere of the 1994 Disney film Angels in the Outfield which, despite being based around the California Angels, paid homage to the original 1951 film, which featured the Pirates in "heavenly" need.[48]

Three Rivers Stadium had a beverage contract with Coca-Cola throughout its history. It was during the Steelers' stay in Three Rivers that the now famous "Mean Joe" Greene Coke commercial aired, leading to a longstanding relationship between the two. When Heinz Field opened, Coca-Cola also assumed the beverage contract for that stadium (the Pirates signed a deal with Pepsi for PNC Park before signing with Coke again in 2014), and also became the primary sponsor for the Steelers' team Hall of Fame, the Coca-Cola Great Hall. After the initial 10-year contract expired, Heinz Field contracted with Pepsi for exclusive pouring rights, breaking a 50-year tradition with the Steelers.

Replacement

[edit]By the early 1990s, multipurpose stadiums had gone out of fashion. They were considered by many to be ugly and obsolete, as well as not financially viable. Joining a wave of sports construction that swept the United States in the 1990s, both the Pirates and Steelers began a push for a new stadium. This eventually culminated in the Regional Renaissance Initiative, an 11-county 1997 voter referendum to raise the sales tax in Pittsburgh's Allegheny County and ten adjacent counties 0.5% for seven years to fund separate new stadiums for the Pirates and Steelers, as well as an expansion of the David L. Lawrence Convention Center and various other local development projects. After being hotly debated throughout the entire southwestern Pennsylvania region the initiative was soundly defeated in all 11 counties; only in Allegheny County was it even close (58-42).

The initiative's defeat led to the development of "Plan B", an alternate funding proposal that used a combination of monies from the Allegheny Regional Asset District (an extra 1% sales tax levied on Allegheny County), state and federal monies and a number of other sources. Despite polls which showed that the public was opposed to this plan as well, on February 3, 1999, the state funding portion of "Plan B" passed the Pennsylvania State House and Senate, clearing the way for construction.

Ground was broken for the new stadiums in 1999.[49][50] On October 1, 2000, the Pirates were defeated 10–9 by the Chicago Cubs in their final game at Three Rivers Stadium.[36] After the game, former Pirate Willie Stargell threw out the ceremonial last pitch (he died the following April hours before the first regular season game was played at PNC Park).[51] Two months later on December 16, 2000, the Steelers concluded play at Three Rivers Stadium, with a 24–3 victory over the Washington Redskins.[52]

Three Rivers Stadium was imploded on February 11, 2001, at 8:03 a.m. on a chilly 21 °F (−6 °C) day. Over 20,000 people viewed the implosion from Point State Park. Another 3,000-4,000 viewing from atop Mount Washington and an uncounted number of people viewed the demolition from various high points across the city. Mark Loizeaux of Controlled Demolition, Inc. pushed the button that set off the 19-second implosion, while Elizabeth and Joseph King pushed the "ceremonial old fashioned dynamite plunger".[53] The demolition cost $5.1 million and used 4,800 pounds (2,180 kg) of explosive.[54][55] With the newly constructed Heinz Field only 80 feet (24 m) away, effects from the blast were a concern. Doug Loizeaux, Mark's younger brother and vice president of Controlled Demolition, Inc., was happy to report that there was no debris within 40 feet (12 m) of Heinz Field.

At the time of the demolition, Three Rivers Stadium still had $27.93 million in debt ($48.1 million today), some of it from the original construction but the rest from renovations in the mid-1980s, bringing more criticism to the public funding of sports stadiums. The debt was finally retired by 2010.[56][57]

Like most stadiums demolished during this time whose replacements were located nearby (including the Civic Arena over a decade later), the site of Three Rivers Stadium mostly became a parking lot. Much like the Pittsburgh Penguins would do with the site of Civic Arena, the Steelers retained development rights to the site of Three Rivers, and would later build Stage AE on portions of the site, as well as an office building that hosts the studios for AT&T SportsNet Pittsburgh, the headquarters of StarKist Tuna, and the regional headquarters of Del Monte Foods. In 2015, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette moved into a new office building also built on a portion on the site after 53 years in the former Pittsburgh Press building and more than two centuries in Downtown.[58]

On September 30, 2012, members of the Society for American Baseball Research marked and painted the home plate and second base of the former stadium on the 40th Anniversary of Roberto Clemente's 3,000th hit. First and third bases could not be marked as the West General Robinson Street now runs over those locations.[59]

On December 23, 2012, on the 40th anniversary of the Immaculate Reception, the Steelers unveiled a monument at the exact spot where Franco Harris made the reception in the parking lot and corresponding sidewalk. The yard lines were also painted on the sidewalks.[60] In the process of marking the yard lines, the second base was accidentally painted over.

In 2022, the faded home plate print and the missing second base was replaced by metal plaques created by the Society for American Baseball Research. The pitcher's mound was also marked for the first time. The new plaques were officially revealed on September 30, 2022, the 50th Anniversary of Roberto Clemente's 3,000th hit.[61] [62]

In 2011, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review reported that the Three Rivers Stadium website was still active, 11 years after the facility's demolition.[63] The newspaper has revisited the issue and reported several times that the website remained active.[64][65] In 2020, nearly twenty years after the stadium had been demolished, the site had finally been taken down due to the domain expiring. However, an archive of the original site still exists, albeit at a different domain name.

Seating capacity

[edit]

|

|

Stadium usage

[edit]Panthers

[edit]The Pitt Panthers played at Three Rivers Stadium on multiple occasions. The Panthers played their full home schedule there for the 2000 season, going 7–4. They played there in the following games:

| Date | Winning Team | Result | Losing Team | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 28, 1974 | #10 Penn State | 31-10 | #18 Pitt Panthers | 48,895 |

| November 22, 1975 | #10 Penn State | 7-6 | #17 Pitt Panthers | 46,846 |

| November 26, 1976 | #1 Pitt Panthers | 24-7 | Penn State | 50,250 |

| September 9, 1982 | #1 Pitt Panthers | 7-6 | #5 North Carolina | 54,449 |

| November 27, 1998 | West Virginia | 52-14 | Pitt Panthers | 42,254 |

| September 2, 2000 | Pitt Panthers | 30-7 | Kent State | 31,089 |

| September 16, 2000 | Pitt Panthers | 12-0 | Penn State | 61,211 |

| September 23, 2000 | Pitt Panthers | 29-17 | Rutgers | 30,890 |

| October 21, 2000 | Pitt Panthers | 42-26 | Boston College | 31,567 |

| November 4, 2000 | North Carolina | 20-17 | Pitt Panthers | 43,872 |

| November 24, 2000 | Pitt Panthers | 38-28 | West Virginia | 46,569 |

Pirates

[edit]Three Rivers Stadium opened on July 16, 1970, but the Pirates lost 3–2 to the Cincinnati Reds in front of 48,846 spectators.[35][66] The first pitch was thrown by Dock Ellis—a strike—to Ty Cline.[67] The first hit in the stadium was by Pittsburgh's Richie Hebner, in the bottom of the first inning.[67] The Pirates lifted their television blackout policy for home games so that local fans could see the inaugural game.[68] The Pirates' lowest season of attendance was 1985, at an average of 9,085.[69] The average attendance would peak in 1991, when the Pirates averaged 25,498 per game.[69] Game one of the 1970 NLCS, at Three Rivers Stadium, was the first postseason baseball game to be played on an artificial surface.[14] The following season, the Pirates advanced to the World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. Three Rivers Stadium hosted game four, in which the Pirates defeated the Orioles in the first night game in the history of the World Series.[14] Pittsburgh hosted its third All-Star Game in 1974. The National League won the game 7–2 and the Pirates' Ken Brett was the winning pitcher.[70] In 1979, the Pirates again won a World Championship, yet again defeating the Baltimore Orioles in a seven-game World Series. Games 3, 4 and 5 of the Series were played at Three Rivers. 15 years later, the midsummer classic returned in 1994. With 59,568 in attendance, the largest crowd to ever attend a baseball game at the stadium,[35] the National League won 8–7 in the tenth inning. On July 6, 1980, the Pirates beat the Chicago Cubs 5–4 in 20 innings—the most innings ever played at the stadium. The longest game at the stadium was played on August 6, 1989, when Jeff King hit a walk-off home run 5 hours and 42 minutes into the 18-inning contest, as the Pirates once again beat the Cubs 5–4.[71] On September 30, 1972, Pirates' right-fielder Roberto Clemente got his 3,000th hit at Three Rivers Stadium, three months before his death.[14]

Only 13 home runs were ever hit into the upper deck of Three Rivers Stadium. Willie Stargell is the all-time leader in upper deck shots at the stadium with four; Jeff Bagwell hit two, while Bob Robertson, Bobby Bonilla, Devon White, Greg Luzinski, Glenallen Hill, Howard Johnson, and Mark Whiten (his home run struck the facade) hit one each.[72]

It was at this venue in 1998 where Sammy Sosa hit his Cub-franchise record 57th homer of the season, besting Hack Wilson, whose record stood for 68 years.

Steelers

[edit]"No matter what happens, when they tear Three Rivers down, a monument ought to be built there. Even if they end up building a hockey rink there, they should put some kind of a monument to that area where the Immaculate Reception took place."

The Pittsburgh Steelers played their first game in Three Rivers Stadium on September 20, 1970—a 19–7 loss to the Houston Oilers.[36] Throughout their 31 seasons in Three Rivers Stadium, the Steelers posted a record of 182–72, including a 13-5 playoff record, and defeated every visiting franchise at least once from the stadium's opening to close, enjoying perfect records there against seven teams. The Steelers sold out every home game from 1972 through the closing of the stadium, a streak which continues through 2008.[74] The largest attendance for a football game was the 1994 AFC Championship Game on January 15, 1995, when 61,545 spectators witnessed the Steelers lose to the San Diego Chargers.[36] On December 23, 1972, Three Rivers Stadium was site to the Immaculate Reception, which became regarded as one of the greatest plays in NFL history.[73] Three Rivers Stadium hosted seven AFC Championship Games from 1972 to 1997;[36][75] the Steelers won four.[76] In the 1995 AFC Championship Game, the Steelers' Randy Fuller deflected a Hail Mary pass intended for Indianapolis Colts receiver Aaron Bailey as time expired, to send the franchise to Super Bowl XXX.[75] A Steelers symbol recognized worldwide, the Terrible Towel debuted on December 27, 1975, at Three Rivers Stadium. The Steelers would move to Heinz Field after it was closed.[77]

References

[edit]- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Experience – Public / Government". Elwood S. Tower Consulting Engineers. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ^ "Three Rivers Stadium". Ballparks.com. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "082517" (PDF).

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on March 21, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "31 Slices of Three Rivers History". Pittsburgh Steelers. Archived from the original on February 25, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Maulers". United States Football League History. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "A Fond Farewell". Sports Illustrated. December 15, 2000. Archived from the original on January 24, 2001. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Mehno 1995, pp. 9

- ^ Leventhal & MacMurray 2000, pp. 52

- ^ a b c d e f g Smith, Curt (2001). Storied Stadiums. New York City: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1187-1.

- ^ Mehno 1995, pp. 9–10

- ^ "Downtown: Images 10: Stadium over the Monongahela". Archived from the original on December 3, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Leventhal & MacMurray 2000, pp. 51

- ^ a b c d e f g Mehno 1995, pp. 10

- ^ Allan, William (June 23, 1961). "B&O agrees on stadium site". Pittsburgh Press. p. 1.

- ^ Seidenberg, Mel (June 24, 1961). "B&O agrees to stadium site". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 1.

- ^ McCollister 1998, pp. 175

- ^ Brem, Ralph (December 8, 1964). "Stadium cost up in final plan". Pittsburgh Press. p. 1.

- ^ "Explain why, Doctor". Pittsburgh Press. (editorial). March 21, 1963. p. 18.

- ^ Uhl, Sherley; Spatter, Sam (April 25, 1968). "Barr urges 'Lawrence' stadium". Pittsburgh Press. p. 1.

- ^ "'David L. Lawrence' gains as name for new stadium". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. April 26, 1968. p. 1, sec.2.

- ^ Hritz, Thomas M. (April 11, 1969). "3 Rivers Stadium is behind schedule". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 1.

- ^ a b Mehno 1995, pp. 13

- ^ Spatter, Sam (February 12, 1969). "'Three Rivers' name of stadium". Pittsburgh Press. p. 66. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Stadium is Named 3 Rivers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. February 13, 1969. p. 27. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Gershman 1993, pp. 224

- ^ a b "It's 'Play Ball' Tonight for Three Rivers lidlifter". Pittsburgh Press. July 16, 1970. p. 1. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "48,846 fans open new stadium". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 17, 1970. p. 1. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Yake, D. Byron (July 16, 1970). "$55,000,000 Three Rivers Stadium tonight replaces..." Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. p. 11. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Jones v. Three Rivers Management Corporation, 483 Pa. 75 (Pa. 1978).

- ^ Gershman 1993, pp. 191

- ^ Cagan, Jonathan; Vogel, Craig M. (2001). Creating Breakthrough Products. FT Press. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-13-969694-7.

- ^ "Pirates to Reduce Stadium Capacity". The New York Times. Associated Press. January 24, 1993. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Leventhal & MacMurray 2000, pp. 50

- ^ a b c d e Gietschier, Steve. "Three Rivers Stadium – (Pittsburgh, 1970–2000)". Sporting News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Spatter, Sam (February 12, 1969). "'Three Rivers' Name of Stadium". Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Mehno 1995, pp. 14

- ^ "Three Rivers Stadium to feature 'no-skin' look". Pittsburgh Press. January 19, 1973. p. 28. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Tuscano, Joe (April 13, 1983). "Yes, things are different at Three Rivers". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. p. B-7. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "CSC TV-5 1983 Pirates Special (Part 2)". YouTube. August 4, 2010. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Stadium lights aren't burning city taxpayers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. September 7, 1970. p. 39. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin, July 24, 1973, Pittsburgh, PA, Three Rivers Stadium". September 22, 2007.

- ^ a b Mehno 1995, pp. 15

- ^ "Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – Google News Archive Search". Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Pittsburgh brings down Three Rivers Stadium". CNN. February 11, 2000. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Adler, Bill Sr. (October 16, 2007). Ask Billy Graham: The World's Best-Loved Preacher Answers Your Most Important Questions. Thomas Nelson. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8499-0310-6. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara (January 24, 2003). "Multi Media: Adrien Brody going darker and deeper". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Steelers Break Ground for New Football Stadium". Pittsburgh Steelers. June 18, 1999. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Tom (April 8, 1999). "City, Pirates break ground for PNC Park with big civic party". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- ^ Finoli, Dave (2006). The Pittsburgh Pirates. Arcadia Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-7385-4915-6.

- ^ "PRO FOOTBALL; Steelers Rout Redskins in Last Three Rivers Game". The New York Times. December 17, 2000. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Barnes, Tom (February 12, 2001). "A Dynamite Drumroll and Three Rivers Stadium Bows Out". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved February 3, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "PLUS: STADIUMS; Three Rivers Is Demolished at 30". The New York Times. February 12, 2001. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Three Rivers Stadium: History". WTAE. Pittsburgh. Associated Press. February 11, 2001. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Pens gone, but Igloo $9.3 million in debt Pittsburgh Tribune-Review (May 14, 2010)

- ^ Three Rivers Stadium: The concrete will crumble but the memories will live on Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (September 29, 2000)

- ^ "Post-Gazette newsroom leaves history Downtown with move to North Side".

- ^ "The Grandstander: Standing with Clemente". September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Steelers unveil Immaculate Reception monument – ESPN". ESPN.com. December 22, 2012. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Pittsburgh, Allegheny County recognize Friday as Roberto Clemente Day". September 30, 2022.

- ^ "Remembering Roberto: Home plate memorial honoring his 3,000th hit to be placed in the North Shore - CBS Pittsburgh". CBS News. September 30, 2022.

- ^ "Three Rivers' virtual afterlife". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. January 23, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "Online Time Capsule". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. February 14, 2015.

- ^ Tribune-Review. "You can still access the Three Rivers Stadium website". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Koppett, Leonard (July 17, 1970). "Pirates Open Their New Park, But Reds Celebrate 3-2 Victory". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Mehno 1995, pp. 42

- ^ Mehno 1995, pp. 8

- ^ a b "Pittsburgh Pirates Attendance, Stadiums and Park Factors". Baseball Reference.com. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Emert, Rich (July 14, 2003). "Where are they now? Brett's All-Star win a big thrill". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Pirates' Long Ball Wins a Long Game". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 7, 1989. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Fun Facts About Pittsburgh's Ball Parks". Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ a b Finder, Chuck. "The house that the 'Immaculate Reception' built". Sporting News. Archived from the original on February 17, 2006. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "Steelers' former radio announcer Myron Cope dies at 79". USA Today. Associated Press. February 28, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "Number three". Pittsburgh Steelers. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ "NFL & Pro Football League Encyclopedia". Pro Football-Reference. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ^ Cope, Myron (2002). Double Yoi! (1st ed.). Sports Publishing, L.L.C. pp. 142–7. ISBN 978-1-58261-548-6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gershman, Michael (1993). Diamonds: The Evolution of the Ballpark. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-61212-5.

- Leventhal, Josh; MacMurray, Jessica (2000). Take Me Out to the Ballpark. New York: Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57912-112-9.

- McCollister, John (1998). The Bucs! The Story of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Lenexa, Kansas: Addax Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-886110-40-3.

- Mehno, John (1995). "History of the Stadium". Pittsburgh Pirates Official 1995 Commemorative Yearbook. Sports Media, Inc.

External links

[edit]- Official website (Archive)

- Thirty Years of Stadium Rock – Pittsburgh Music History

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette story on opening

- July 17, 1970 Pittsburgh Press

- July 16, 1970 Pittsburgh Press

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Home of the Pittsburgh Pirates 1970 – 2000 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Pittsburgh Steelers 1970 – 2000 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Pittsburgh Panthers 2000 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of the MLB All-Star Game 1974 1994 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of AFC Championship Game 1973 1976 1979–1980 1995–1996 1998 |

Succeeded by |

- Sports venues completed in 1970

- Sports venues destroyed in 2001

- American football venues in Pennsylvania

- Baseball venues in Pennsylvania

- Multi-purpose stadiums in the United States

- Defunct National Football League venues

- Defunct college football venues

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- Defunct American football venues in the United States

- Defunct baseball venues in the United States

- Defunct multi-purpose stadiums in the United States

- United States Football League venues

- Sports venues in Pittsburgh

- Pittsburgh Pirates stadiums

- Pittsburgh Steelers stadiums

- Pittsburgh Panthers football venues

- Demolished buildings and structures in Pittsburgh

- Demolished sports venues in Pennsylvania

- 1970 establishments in Pennsylvania

- 2000 disestablishments in Pennsylvania

- Buildings and structures demolished by controlled implosion

- Pittsburgh Maulers stadiums